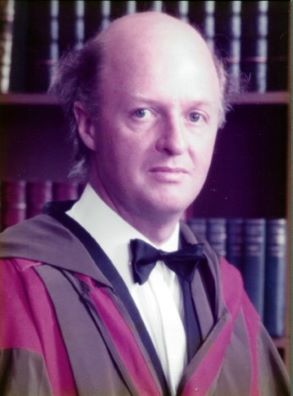

Lawrence Theodore Threadgold (02nd

September 1927 - 13th Aug 2021).

Lawrence T. Threadgold was Professor

of Parasitology in the Department of Zoology, Queen’s University, Belfast, from

1978 until his retirement in 1985, serving as Head of Department from 1979 until

1985. He first joined Queen’s University in 1956 as Lecturer in Zoology. He first

joined Queen’s University in 1956 as Lecturer in Zoology but undertook a

post-doctoral fellowship in the University of Western Ontario from 1956 until

1958, and a Lectureship in the Medical School of the University of Nova Scotia

from 1958-1960, where his remit was Embryology. He was also honoured with a Visiting Fellowship to Rice

University, Houston, Texas in 1967-68.

Entering

Trinity College Dublin (TCD) in 1948, he enlisted as a student of Natural

Sciences taking Geography, Geology and Zoology. Thanks largely to the

enthusiastic and inspirational guidance of J. D. Smyth, who was at that time a

Lecturer in Zoology with a fervent interest in parasite physiology, he chose to

complete his BA in Natural Sciences by specialising in Zoology. Incidentally,

in TCD he shared rooms with William C. Campbell, and both were to become

lifelong friends. In due course Lawrence completed a PhD in avian reproductive

physiology, before moving to Belfast to set up home there with his wife Jenny, a

Trinity graduate with a particular interest in Modern Languages.

Lawrence’s output of high-quality research publications places him

as one of the founders of modern Parasitology, a fact recognised by the British

Society for Parasitology, in admitting him to the Honorary Membership, and by

Trinity College, in the award of a DSc degree in 1976. He was rightly regarded as the world’s leading

authority on parasite ultrastructure, and his numerous peer-reviewed

publications are still widely quoted in reviews. His unique

insight into fluke ultrastructure revealed that the surface layer of the

parasite – that part in direct contact with the host tissues - is not, as had

formerly been thought, an inert ‘cuticle’ like that of the nematode parasites.

Instead, it is a living cytoplasmic layer, limited by a surface cell membrane,

but lacking division into individual cells – technically a ‘syncytium’.

Physiologically, it is highly active with numerous roles, allowing the parasite

to survive in what is, in effect, a hostile environment. Subsequently, the

surface specialisation of liver flukes has been shown to be shared by all other

fluke and tapeworm parasites, including the highly pathogenic human blood

flukes, the schistosomes, which are amongst most damaging and prevalent of

human parasites in the tropics.

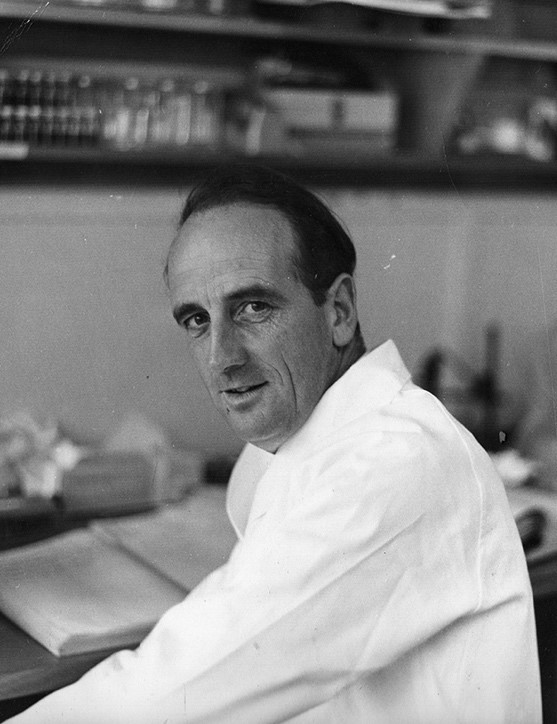

It is a

feature of Lawrence’s publications that all are illustrated by exquisite line

diagrams and electron micrographs of the highest quality that clarify complex

anatomical details and relationships in a way that text descriptions cannot

easily achieve. The high quality of his electron micrographs set the standard

for international peer-reviewed publications in Parasitology at the time. Lawrence’s magnum opus was, however, the book he published

in 1967, second edition in 1976, entitled ‘The Ultrastructure of the Animal

Cell’ which lavishly illustrated by his enlightening diagrams, complementing

his concise and elegant text.

Lawrence was an exceptional and inspiring

teacher, and the kindest and most supportive advisor and colleague one could

hope to have. He truly inspired a generation of scientists in his subject area,

and his influence continues to the present. He will be long remembered for his

seminal contributions to Parasitology, his wit, wisdom and conviviality as a

teacher and supervisor.

By Prof. Robert (Bob) Hanna, Agricultural,

Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI), Belfast, NI; Honorary Professor at

Queen’s University Belfast.